top of page

Unit 6: Civil War and Reconstruction

Standards: *SS8H5,*H6 and E2c. (*means prioritized standards)

-

Vocabulary Practice Set: https://quizlet.com/_4vs1ub

-

Vocabulary Knowledge Rating Sheet:

-

K.I.M Vocabulary Practice:

-

Virtual Fieldtrips: "Andersonville"/Unit 6

-

*H5b. http://www.gpb.org/education/georgia-studies/virtual-field-trips

-

Video Resources:

-

Georgia Stories: Thomasville – Playground of the Northern Industrialists

-

H5a. Summary Graphic Organizer/Study Guide

-

Enrichment: H5A. ONLY after you completely understand how slavery was one of the causes of the civil war. (North v. South)

Youtube Videos to reinforce your learning

****SS8H5 a. Explain the importance of key issues and events that led to the Civil War; include slavery, states’ rights, nullification, Compromise of 1850 and the Georgia Platform, the Dred Scott case, Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, and the debate over secession in Georgia.

The Civil War is likely the most researched and analyzed period of American history. The causes, events, and outcomes still impact and resonate with Americans today.

Georgia’s role in the years leading up to the war, during the war itself, and during Reconstruction was significant. Slow to secede from the Union, this slave-holding state encouraged compromise through the Georgia Platform when confronted with the Compromise of 1850. Even after Abraham Lincoln was elected, the state had a heated debate between those legislators who were for and those who were against leaving the Union. A well-known opponent of secession was Georgia’s own Alexander Stephens. Interestingly, Stephens became vice-president of the Confederate States after Georgia decided to leave the union with the rest of the Deep South.

During the war, Georgia produced much of the manufactured equipment for the Confederate States of America (CSA). For a large portion of the war, Georgia remained relatively untouched by US forces. However, once Grant and Sherman set their sights on the state, it suffered tremendously during Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign and March to the Sea. After the war, Georgia’s economy was devastated and there was much suffering throughout the state.

The intent of this standard is for students to be able to explain the importance of the key issues and events that led to the Civil War. They should be able to discuss some of the important events that happened during the Civil War.

Due to the rules of the Trustees, slavery was not allowed in Georgia until the early 1750’s. Once it was legalized, slavery grew quickly due to Georgia’s agriculture-based economy. However, slavery grew exponentially with the invention of the cotton gin. The South’s economic dependence on cotton led to a change of attitude about the evils of slavery. While many of the nation’s founding fathers disliked slavery, and hoped that later generations would find a way to end it, their sons and grandsons began to defend slavery as a necessary good and began infringing on the rights of those who spoke out against it in the South.

In turn, many in the North, led by the writings of abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, began to despise slavery and call for its end. Others simply became uncomfortable with its existence in the nation’s borders and disagreed with its expansion.

The gap between the two regions widened every time the U.S. gained more territory. The South hoped for slavery to expand into the new territories while many in the North wanted it, at the very least, to be contained to where it already existed. As with the other slave states, Georgia wanted slavery to expand and was distrustful of the abolitionist movement taking place in the North.

A major conflict in the history of the United States, from its creation to the present, is the issue of states’ rights. States’ rights regard the amount of power a state government has in relation to the amount of power held by the federal government in making decisions. Early in the United States’ history, the Articles of Confederation gave the individual states too much power and the nation could not even tax the states for revenue. All of the signers of the U.S. Constitution knew that the federal government needed to have more power than it had under the Articles of Confederation to run the country effectively. However, once the Constitution was ratified, there were several instances before the Civil War that caused the country to almost break apart due to the issue of states’ rights. While the argument for states’ rights during the Civil War was often based on a state’s right to have slavery, there were other times in the nation’s history that issues tied to states’ rights became major concerns. For example, during the War of 1812 there was talk in New England about secession. This was due to the fact that the New England states were losing money with their inability to trade with Britain.

A states’ rights issue, the nullification crisis in the early 1830’s, was a dispute over tariffs. The North supported high tariffs to subsidize their fledgling manufacturing industry against the cheaper products that could be sent to the United States by Great Britain. The South was opposed to this tariff because it took away profits from cotton farmers based on Great Britain’s retaliatory tariff on cotton. When the Northern states, who dominated the House of Representatives, voted to renew the tariff, South Carolina threatened to nullify the tariff and even possibly secede. However, Andrew Jackson’s threat to attack South Carolina if they attempted to leave the union worked well enough to keep the state in the fold for the time being.

Another states’ rights issue occurred in Georgia. Georgia lost the Worcester v. Georgia case but refused to release the missionaries or stop pushing for Cherokee removal. This test of states’ rights proved that a state could do as it pleased if there was not a unified attempt to by the federal government or other states to stop them.

The issues of slavery, tied with the concept of states’ rights, left a huge rift in the country. Controversy after controversy widened this gap, and for almost 40 years, members of the U.S. Congress tried to close wounds with compromises and acts that amounted to temporary Band-Aids. Though these acts and compromises kept the country together in the short term, as Abraham Lincoln said “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” Over time, a physical war between the North and South appeared to be almost inevitable.

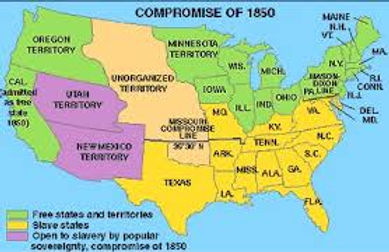

The first compromise was called the Missouri Compromise, an agreement between the northern and southern states about allowing Missouri to enter the Union. The issue with this compromise focused on disrupting the balance of power between the slave and free states in Congress. Allowing Missouri to enter as a slave state and Maine to enter as a free state enabled the balance of power to remain the same for almost 30 years as states were entered into the Union in free and slave pairings. This pattern changed in 1850 when California, due to the Gold Rush, had a population large enough to apply for statehood. With no slave state available to balance the entry of a free one, major conflict ensued between the North and South. The South, which had a smaller population than the North, was fearful that losing the balance of power in the Senate would one day give the North the opportunity to end slavery. Talk of secession was prevalent in the South and the Civil War almost started a decade earlier than it did. However, Senators Henry Clay and Stephen A. Douglas wrote the Compromise of 1850, a bill that both groups grudgingly agreed to approve.

Though there were several provisions in the Compromise of 1850, the two most important were that California was admitted as a free state resulting in a power imbalance in both the House and Senate. In turn, Northern congressmen agreed to pass the Fugitive Slave Act, which guaranteed the return of any runaway slaves to their owners if they were caught in the North. There was much protest in the North to this act but the southern leaders believed it would protect the institution of slavery.

While debate over the Compromise of 1850 was raging in Congress, prominent Georgia politicians were deciding if the state should accept the terms of the Compromise. If passed, it would give the free states more representation in the US Senate and end the balance of power that had been established for 30 years. Led by Alexander Stephens, Robert Toombs, and the promise of the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, Georgia provided a response to the compromise, known as the Georgia Platform. This document outlined southern rights as well as the South’s devotion to the Union. It established Georgia’s conditional acceptance of the Compromise of 1850. With Georgia leading the way, other southern states also accepted the Compromise preventing a civil war for 11 years.

The Dred Scott Case (1857) ended in a Supreme Court ruling that greatly favored the southern view of slavery and lead to a greater ideological divide between the North and South. Dred Scott was a slave who was taken by his master to the free states of Illinois and Wisconsin. Upon his return to Missouri, Scott sued the state based on the belief that his time spent in the free states made him a free man. When the case made it to the Supreme Court, the court ruled on the side of Missouri. The Court went on to declare that slaves and freed blacks were not citizens of the United States and did not have the right to sue in the first place. It’s interesting to note that Georgia native, Justice James Moore Wayne, was instrumental in rendering this decision as he concurred with Chief Justice Taney. Maintaining his loyalty to the United States, Wayne remained on the Court for the duration of the war even though the Confederacy deemed him a traitor and seized his property. He was the only justice from the Deep South to remain on the Court during the war years.

The final situation that plunged the United States into the Civil War was Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860. Due to the dramatic sectionalism that was dividing the country, four presidential candidates ran for office in 1860. These men were Abraham Lincoln, John Breckenridge, John Bell, and Stephen Douglas. Because of the issue of slavery, Northern and Southern Democrats split into two parties with the nominee for the North being Stephen Douglas and the nominee for the South was John Breckenridge. John Bell was the candidate for the Constitutional Union Party whose primary concern was to avoid secession. Lincoln was the nominee of the Republican Party, a party that began in 1854 and whose primary goal was to prevent the expansion of slavery. Georgia would ultimately stand with candidate John Breckenridge. Lincoln was not on the ballot in Georgia as he was not in most southern states.

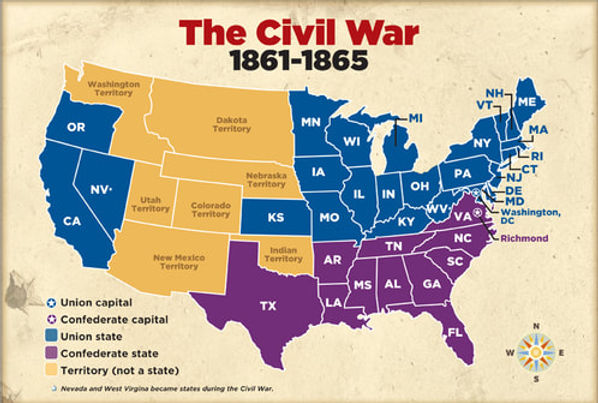

Lincoln won the election of 1860 with 180 electoral votes (152 electoral votes were needed to win at that time). After the election, the southern states, believing that Lincoln’s ultimate goal was to end slavery, voted one by one to secede from the Union. Georgia, after a three-day debate, voted to leave the Union on January 19, 1861.

In 1861, there was a spirited debate over secession in the Georgia General Assembly to determine if Georgia should join its southern brethren in breaking away from the Union. Though there were strong supporters for both sides of the issue, Georgia eventually seceded from the Union after several other southern states. Georgia was part of the Confederacy from 1861-1865.

During the debate, there were those who did not want to leave the Union, including representatives from the northern counties, small farmers and non-slave holders, and most importantly Alexander Stephens, who gave an eloquent speech against secession. On the other side, were large farmers and slave holders, Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown, and powerful and influential men such as Robert Toombs, who had a social and economic stake in the continuation of the institution of slavery. In an early vote for secession, the Assembly was split 166 to 130 in favor of secession. However, in the end, the General Assembly voted 208 to 89 in favor of seceding from the union.

As information: Alexander Stephens (1812-1873) served as Governor of Georgia, U.S. Congressman, U.S. Senator, and the Vice-President of the Confederacy. Stephens, though physically small and frail, was a major force in Georgia and U.S. politics. Born in Crawfordville, he graduated from the University of Georgia in 1832. In 1836, soon after passing the Georgia Bar, Stephens was elected to the Georgia Assembly where he served as a member of the Whig party.

In 1843, Stephens was elected to the U.S. Congress. While in Congress, Stephens played a major role in assisting with the passage of the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Though an advocate for slavery, Stephens was a Unionist who resisted secession until the very end.

After the election of 1860 and the secession debate in Georgia, Stephens remained the strongest advocate for staying with the United States. However, once the General Assembly voted for secession, Stephens signed the “Ordinance of Secession” and was immediately chosen as one of Georgia’s representatives to the Confederate Congress. At the Congress, he was elected vice president of the Confederate States of America. His election was due to his political experience and as a sign of Confederate unity based on his Unionist past. Stephens had a frustrating experience as the vice-president; though a brilliant statesman, his weak stature never allowed him any military experience. Once the CSA’s focus turned to military engagement, Stephens had little to do.

***Causes Review Game Zone

After the war, Stephens was jailed for five months. Upon his release, the people of Georgia elected him as their U.S. Senator. However, the Senate Republicans refused to sit the former C.S.A. vice president so soon after the war was over. Stephens spent the next few years writing. He was elected to the U.S. House again in 1877, where he served until 1882. He was elected Governor of Georgia in 1882, but died shortly after. Stephens County is named in his honor. ****Causes of the Civil War Matching Game

****SS8H5 b. Explain Georgia’s role in the Civil War; include the Union blockade of Georgia’s coast, the Emancipation Proclamation, Chickamauga, Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, Sherman’s March to the Sea, and Andersonville.

In this standard, students should focus on the role of Georgia during the Civil War. While it may be helpful to student understanding to relate national events of the war period, the focus should be on Georgia’s involvement in the war effort.

One of the United States’ most important strategies during the Civil War is often called the Union Blockade of Georgia’s coast. The North’s primary objective was to use its superior navy to prevent the South from shipping its cotton to England and France in return for weapons and other supplies. General Winfield Scott was the mastermind behind the strategy, often called the “Anaconda Plan” due to its intention of “squeezing” the CSA to death. The press dubbed it the “Anaconda Plan” as a critique, believing it to be too passive and too difficult and slow to implement. Despite initial criticisms, this strategy proved to be a factor in the US victory.

At first, the Union blockade was not successful and almost nine out of ten “blockade runners,” private citizens who took the risk of evading the Union blockade for the chance at huge profits, were able to make it to Europe and back. However, things changed dramatically in Georgia when the North destroyed the brick Fort Pulaski with rifled-barrel cannon. Once this fort was destroyed, the North was able to effectively restrict continued to attempt to sneak past the Union blockade, and build several gun boats, including three “ironclads,” Georgia was unable to effectively deal with the power of the Union Navy. The US also made several attacks on Georgia, including occupying St. Simons Island and attacking the port town of Darien. Savannah was finally captured by General William T. Sherman, in 1864, with assistance from the U.S. Navy which was operating in the port.

The Battle of Antietam (1862), the bloodiest one day battle of the Civil War and considered a draw with no clear winner, was the “victory” Abraham Lincoln needed to release his Emancipation Proclamation. One week after this battle, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. Though often understood as the document that “freed the slaves,” the Proclamation actually said that all slaves in the rebellious states would be freed on January 1, 1863. At that point, all slaves in states that fought with the Union were not freed. Hypothetically, according to this document, if the South had surrendered before January 1, they would have been allowed to keep their slaves. However, Lincoln knew the CSA would not give up, and this document would end slavery once the war was over. It would also be the moral issue that discouraged other European powers from involvement in the Civil War.

For the first three years of the Civil War, Georgia was virtually left untouched by the war. There were a few skirmishes, though the Battle of Fort Pulaski in 1862 led to the North’s control of the Georgia coast and expansion of the Union Blockade of Southern ports. However, the major impact of war arrived on Georgia’s doorstep in 1863, during the Battle of Chickamauga. The town of Chickamauga is located in Walker County just 10 miles south of the Tennessee/Georgia line. The battle lasted three days from September 18-20 and was the second bloodiest battle of the Civil War with over 34,000 casualties. The battle was the largest ever fought in the state of Georgia.

The Generals that led this battle were William S. Rosecrans of the USA and Braxton Bragg of the CSA. This battle was part of a larger Northern objective to capture the city of Chattanooga, itself an important rail center, and to use its capture as a stepping stone to capture a more significant rail road hub: Atlanta. While Rosecrans captured Chattanooga earlier that September, he wanted to circle around Bragg’s army and cut the Southern supply lines in Western Tennessee and Northwest Georgia. However, the CSA discovered Rosecrans’s army in the area and attacked.

This battle is significant for several reasons. It was the largest Union defeat in the Western theater of the Civil War. After the battle, Bragg, who was preoccupied with his enormous losses, failed to follow the Union forces back into Chattanooga. Eventually, the Confederates turned their attention to Chattanooga but were soundly defeated by Union troops and reinforcements under the leadership of General Ulysses Grant. This southern defeat provided Grant the stepping stone which led to his promotion to the Commanding General of the U.S. Army. Once Chattanooga was defended and securely in Union hands, it was used as a launching point for Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign.

To many Georgians, General William T. Sherman’s actions during the Civil War make him the most hated figure in the state’s history. However, many historians are re-examining Sherman’s military campaigns and are developing varying viewpoints about the purposes and rationales behind his treatment of the South. No matter if Sherman was a truly a tyrant who reveled in his “mistreatment” of Georgia, or simply a military commander doing his job to swiftly end the war, Sherman’s military campaigns through Georgia left an enormous impact on the social, economic and political history of the state.

Though often called “Sherman’s March through Georgia” or simply “Sherman’s March,” Sherman actually led two separate military campaigns in the state. The first was called the Atlanta Campaign. Beginning in the spring of 1864, Sherman set out to capture Atlanta. Capturing the city would bring a devastating blow to the Confederacy because Atlanta’s was the major railroad hub of the South and had adequate industrial capabilities. The campaign took almost four and one-half months and several major engagements took place between the two armies including the Battles of Dalton, Resaca, and Kennesaw Mountain.

The Southern army was led by General Joseph Johnston who believed that, with his army being out numbered almost two to one, he should use defensive tactics to slow down Sherman’s aggressive campaign. He hoped to have his army dig in to defensive positions and lure Sherman into costly head-on attacks. However, with the exception of the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, where the North lost over 2,000 men, Sherman chose to simply go around (“out-flank”) the CSA’s positions and continue to move toward Atlanta forcing the CSA to withdraw from their defensive strongholds.

As Sherman pushed his army closer and closer to Atlanta, CSA President Jefferson Davis removed Johnston from command and replaced him with General John B. Hood, who would attack Sherman’s larger army headon in order to protect the city. Though Hood did as ordered, his attacks were unsuccessful and did not deter Sherman and his movements toward Atlanta. It should be pointed out that there was not one major battle to take Atlanta but instead several small battles that eventually allowed Sherman the opportunity to move close enough to the city to bombard it with cannon fire. These battles include the Battle of Peachtree Creek (July 20, 1864), the Battle of Atlanta (July 22, 1864), and the Battle of Ezra Church (July 24, 1864).

On September 2, 1864, General Hood was forced to withdraw from Atlanta, leaving the city open to Union occupation. Sherman held the city for more than two months, while planning for what was to be the March to the Sea. On Nov 15, 1864, Sherman’s army left Atlanta. Whether or not the Union army was solely to blame for the fire that spread through the city as it was withdrawing, or if some of the fires were started by Confederate soldiers or civilians, is a topic that has been debated from almost as soon as it happened. Regardless, as Sherman started his new campaign, the city of Atlanta was left smoldering and in ruins. The capture of Atlanta in September of 1864 was critical, not only due to Atlanta’s industrial role for the South, but also because it gave the war weary North a victory to celebrate and boosted the will-power to continue fighting. With Sherman’s victory, Lincoln was assured a triumph in the 1864 presidential election.

After leaving the city of Atlanta utterly destroyed, Sherman set his sights on the rest of Georgia. Hoping to end the war as quickly as possible, while punishing the South for starting the war, Sherman began his infamous March to the Sea. The march began on November 15, 1864, and ended on December 21, 1864, with Sherman’s capture of Savannah. Due to the losses, the CSA sustained during the battles of the Atlanta campaign, and Hood’s attempt to lure Sherman out of Georgia by marching toward Tennessee, Union troops had an unobstructed path to the Atlantic Ocean.

During the march, Sherman’s army implemented the Union’s hard-war philosophy, creating a path of destruction that was 300 miles long and 60 miles wide. His plan to wreak havoc on Georgia’s infrastructure (railroads [Sherman’s neckties], roads, cotton gins and mills, warehouses) that assisted in supplying Confederate troops was intentional and deliberate. However, it is widely disputed about how Union soldiers were ordered to behave during the march. Per written orders from Sherman before leaving Atlanta, Union troops were permitted to “forage liberally on the countryside”, but were prohibited from trespassing and entering homes. Sherman’s ill-disciplined men burned buildings and factories, looted civilian food supplies and took civilian valuables as treasures of the march. Modern historians believe that violent aggression was not the norm, but rather the exception. Sherman’s lack of tolerance of violence led to prosecution but, there is ample evidence that the invading army often intimidated Georgians. Sherman believed that destroying the morale of Georgians would lead to a quick end of the war.

The only major infantry battle during the march happened at Griswoldville, a small town that produced the Colt Navy Revolver. Sherman’s men encountered a Georgia militia unit comprised of men too old and boys too young for service in the regular army. The rather lopsided result (Union losses: 62 soldiers v. Georgia militia losses: over 650 men and boys) allowed Sherman’s forces to continue their move toward Savannah. Calvary skirmishes along the way resulted in the same, an unobstructed path toward the port city. In the end, Savannah, not wanting to receive the same bombardment and destruction that beset Atlanta, surrendered to Sherman without a fight on December 22, 1864. Sherman wrote to Abraham Lincoln that Savannah was his Christmas present (along with about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton that was ultimately shipped to Northern factories).

Andersonville Prison is the most notorious prisoner of war camp from the Civil War era. Located in Macon County, the prison’s official name was “Fort Sumter” but became known as Andersonville after a nearby railroad station. Built to hold only 10,000 Union prisoners of war in 1864, the camp’s population tripled to over 30,000 at the peak of its occupancy.

Once the prison began to reach its occupancy limits, the main water source, a small creek that flowed through the camp, became infested with diseased human waste and other sewage. This encouraged disease to spread rapidly throughout the prison camp. In addition, due to the success of the Union blockade, the South was running low on food and other supplies for the prisoners. Finally, the Union prisoners turned on each other and a group of soldiers known as “the raiders” terrorized the fellow prisoners by robbing and beating them. Their crimes were countered by the regulators, a band of men who tried to stop the raiders. Six of these raiders were later hanged for their crimes. With these horrible conditions, more men died (over 13,000) at Andersonville than at any other Civil War prison. Due to the awful conditions, Captain Henry Wirz, the commander of the camp, was executed by the North for war crimes. He was the only CSA official to meet this fate. While some supported Wirz’s execution due to the harsh treatment of the Andersonville prisoners and the high death rate, others believed that Wirz did what he could to run the prison with the South’s lack of resources and the decision by his superiors to continue sending prisoners to the already overcrowded prison. There was an effort to relieve the overcrowded conditions at Andersonville by building Camp Lawton near Millen, Georgia, but the advancing of Sherman’s army through southeast Georgia kept the CSA from moving men from Andersonville to the less crowded location.

****SS8H6 a. Explain the roles of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments in Reconstruction.

****SS8H6 b. Explain the key features of the Lincoln, the Johnson, and the Congressional Reconstruction plans.

From 1865–1872, three Reconstruction plans were enacted in Georgia and three Constitutional amendments were intertwined with these plans. Therefore, standard elements A and B will be addressed together.

The first Reconstruction phase was called Presidential Reconstruction (1865-1866). During this plan, President Andrew Johnson, a native of Tennessee who remained loyal to the Union, was extremely lenient with the Southern states. His plan, based on that of Abraham Lincoln who had been assassinated in April of 1865, allowed the South readmission into the Union if 10% of the population swore an oath of allegiance to the United States. They also were required to ratify the 13th amendment, which officially ended slavery in the United States.

Georgia, taking advantage of this moderate policy, held a constitutional convention in 1866 to secure readmission to the Union. In the new state Constitution, the Ordinance of Secession was repealed and the convention passed the 13th amendment. However, the Constitution was very similar to the one that of the Secessionist Constitution of 1861, including an amendment banning interracial marriage. Nonetheless, because the state passed the 13th amendment, Georgia was readmitted into the Union in December of 1865. This proved to be a temporary situation.

Trouble began brewing again between the Southern states and the Republican controlled Congress when several former Confederate leaders were elected back into the state and national governments. In Georgia, former CSA Vice President Alexander Stephens, and CSA Senator Hershel Johnson, were elected Georgia’s two U.S. Senators. Northern Senators, especially those called Radical Republicans, who favored harsher punishments for the South, were aghast at having these high-ranking CSA officials in Congress and refused to seat them. Additionally, there began to be calls against President Johnson for abuse of power and proceedings for his impeachment started to take place.

Finally, the Radical Republicans were appalled at the South’s treatment of the freedmen under laws that were known as Black Codes. Under these laws, blacks were not allowed to vote, testify against whites in court, and could not serve as jurors. With the South’s treatment of Blacks, the Congress introduced the 14th amendment which made African-Americans citizens of the United States and required that they were given the same rights as all U.S. citizens.

The next plan was called Congressional Reconstruction (1866- 1867). Georgia, along with the other Southern states, refused to ratify the 14th amendment. With this action, Georgia and the rest of the South was placed under the authority of Congress. As a result, Southern states were required to pass this amendment in order to be readmitted into the Union. With the South continuing to refuse to pass this amendment, along with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867. This act created five military districts in the South, with Georgia, Alabama, and Florida making up the third district.

Under Military Reconstruction General John Pope served as the third district’s first military governor. During this period, Georgia held another constitutional convention, this time in Atlanta. Atlanta was chosen because it was more accepting of the state’s Republican delegates along with the 37 African American delegates that had been elected to serve in the convention. During this convention, Georgia created a new constitution that included a provision for Black voting, public schools, and moving the capital to Atlanta.

After this convention, Republican Rufus Bullock was elected Governor and the Republican-controlled General Assembly began its session. However, the military continued to be a presence in the state due to the continued actions of the Ku Klux Klan and Georgia’s refusal to pass the 15th amendment which gave African-American men the right to vote. Georgia was finally readmitted into the Union in 1870 when reinstated Republican and black legislators voted for the passage of the 15th amendment. However, by 1872 southern Democrats called the redeemers were voted back into office and took control of the Governorship and General Assembly.

****SS8H6 c. Compare and contrast the goals and outcomes of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Ku Klux Klan.

During the Reconstruction period, two organizations emerged that would have an impact on the newly freed slaves. The Freedmen’s Bureau was designed to give freedmen and poor whites an economic boost and an opportunity to learn to read and write through formal education. On the other hand, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) terrorized freedmen through violence and intimidation. By burning schools and intimidating freedmen, the KKK was at odds with the economic and social improvement desired by the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, officially titled “The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands,” was created to help African-Americans adjust to their newly gained freedom. This program also supported poor whites in the South. The program provided food to whites and blacks who were affected by the war, helped build freedmen’s schools and hospitals, and supervised labor contracts, and other legal disputes. Overall, the Freedmen’s Bureau was moderately successful. During its early years, the organization fed, clothed, and offered shelter to those most harshly affected by the war. There were also successes in its education programs. The Freemen’s Bureau created the first public school program for either blacks or whites in the state and set the stage for Georgia’s modern public school system. In addition, some of the schools created by the Freemen’s Bureau continue to this day throughout the South, including two of Atlanta’s historical black colleges: Clarke Atlanta University and Morehouse College.

Note: The common view concerning the Freedmen’s schools were that they were almost completely created by northerners and staffed primarily by white, northern women. However, Dr. Ronald E. Butchart, from the University of Georgia, has concluded that almost 1/5 of the teachers in the Freedmen’s schools were native Georgians of both races.

The first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) began in 1867 in Tennessee and was a loosely governed organization consisting mostly of Confederate veterans. This group began as a social club for former Confederate soldiers; however, they became progressively more political and violent. Soon after their creation, they began to use terroristic actions to intimidate freed blacks and white Republicans (derogatorily called Carpetbaggers for those whites who moved from the North, and Scalawags, the Carpetbagger’s white allies from the South) from voting and running for office during the Reconstruction period. Using tactics of intimidation, physical violence and murder against Blacks, the KKK tormented Black organizations such as the Freedmen schools and churches in hopes of establishing social control over African Americans or Blacks and their white allies.

The KKK was successful in their political goals as Democrats gained control of Georgia politics in 1871. Many of the Democrats were members of the Klan, such as former Civil War soldier John B. Gordon. It was over 100 years before Republicans gained a foothold in the state again. Socially, the KKK often used severe acts of violence against the freedmen. In some cases, African Americans or Blacks rebuilt burned schools and churches, and sometimes even fought back when attacked. Nonetheless, the KKK was a major force in the state during the Reconstruction Period and the white supremacy and racial segregation they championed became the norm in Georgia, and the rest of the South, for several decades.

The first KKK disbanded around 1871, when Democrats started to regain political control of the state and Congress passed the Force Act of 1870 and Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also called the Ku Klux Klan Act). These acts authorized federal authority to fight and arrest members of the Klan. The Klan resurfaced in its second incarnation in 1915 after the death of Mary Phagan.

****SS8H6 d. Examine reasons for and effects of the removal of African American or Black legislators from the Georgia General Assembly during Reconstruction. ***3 Different Reconstruction Plans Video link***

For a brief period during Reconstruction, African American or Black freedmen were given more political rights than they had ever had and would not have again for 100 years. Primarily, the freedmen were given the right to vote. With this freedom, 32 African Americans or Blacks were elected to the Georgia General Assembly in 1867. However, within days of convening of the General Assembly, these African American or Black legislators were expelled from the legislature.

The reasons for the expulsion of the African American or Black legislators were numerous (click for video). As recorded in the Journal of the Senate in 1868, the African Americans or Blacks were simply “persons of color” and, as “non-citizens”, were not entitled to hold office under Georgia’s Constitution. Georgia’s Democratic legislators scoured the state Constitution for any passage that supported the expulsion. Some of the expelled legislators were said to be ineligible for a variety of reasons and were summarily discredited by extreme judgements on their personal characters. Examples included Senator A. A. Bradley, who was declared ineligible due to his conviction in New York for “seduction” (the Georgia Supreme Court later ruled him innocent of the charges). Senator George Wallace was said to be illiterate. Representative J. T. Costin was determined to be a non-resident of the county for which he was elected. Representative Henry M. Turner was framed for unethical practices while serving as postmaster of Macon. Republican friends of the African American or Black legislators were not numerically strong enough to prevent the expulsion. When the two houses of the General Assembly brought the vote for removal to the floors of the chambers, some Republicans voted with the Democrats to ensure that their removal would happen. Four members, considered to be mulattos (persons of mixed black and white ancestry), were allowed to retain their seats because their African American or Black ancestry could not be proven.

The effects of the removal were far-reaching. Republican Governor Rufus Bullock was at odds with the removal and expressed indignation at the action. He ultimately took the expulsion case to Congress, soliciting their help to reinstate the legislators. Led by Robert Toombs, Bullock was censured (an official expression of disapproval) by Georgia’s political leaders due to his attempt to un-do the expulsion. As a result of the expulsion, in the eyes of the U. S. Congress, Georgia remained unreconstructed and was not granted legal return to the United States. The ousted African Americans or Blacks also appealed to Congress for federal intervention before Georgia could be readmitted to the Union.

Dissenting opinions on the questions of removal and reinstatement were printed in Georgia newspapers, also stirring up strong feelings about the action throughout the country. Some papers believed that the courts should render a decision in a test court case and that the decision should be final. Other papers believed that each body of the General Assembly should be the sole judge regarding the eligibility of its members. Through the media of the day, the entire country was agitated by the “act of hostility on the part of the Georgia Legislature.” Georgia was negatively compared to other Southern states as a result.

Meanwhile, African American and Black political leaders suffered “outrages” (an act of wanton cruelty or violence; any gross violation of law or decency). Representative A. Colby was removed from his home and beaten after he requested military protection for a Freedmen’s school. Representative Alf Richardson was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. Purported charges of rape, murder, and the use of counterfeit money by the African American or Black political leaders kept them at odds with the white population. They were constantly harassed and threatened by the Klan.

African American or Black leaders met in Macon, Georgia in 1868 in a Colored State Convention. Over 135 delegates representing 82 counties met to criticize the Legislature, calling it “illegal and revolutionary.” The main purpose of the convention, however, was to inform the freedmen of the political standing and to offer guidance for the upcoming fall election. Another meeting was scheduled to occur in Southwest Georgia in the town of Camilla. Ousted Representative Philip Joiner led over 200 African Americans or Blacks on a 25-mile march from Albany to Camilla to attend a Republican political rally. Locals in Camilla, who were determined that the Republican rally would not happen, ambushed the marchers as they arrived in Camilla, killing almost a dozen marchers and wounding over 30 others. News of the Camilla Massacre shaped the state and national opinions about the fall elections, causing both Republicans and Democrats to solidify their positions about the 1868 Presidential election. The violence at Camilla intimidated many African Americans or Blacks from participating in the election. In some places, like Albany, African American or Black votes were either destroyed or changed to Democratic votes (Georgia did not use the secret ballot at that time). Republican members of Congress were appalled at the violence and fraud and required Georgia to once more undergo military rule and Radical Reconstruction.

The postponement of restoring Georgia to the United States was delayed as the state was placed under military control per the Georgia Bill. In December, 1869, Federal troops, under the leadership of General Alfred H. Terry, returned to Georgia. Terry ordered the removal of the General Assembly’s ex-Confederates (24 Democrats who could not pass the test-oath about returning to the Union) and replaced them with Republican runners-up. This was known as Terry’s Purge. The expelled African American or Black legislators were reinstated, thus creating a heavy Republican majority in the legislature. By early 1870, Georgia’s General Assembly ratified the Fifteenth Amendment and chose new Senators to send to Washington. In July, 1870, Georgia was readmitted to the Union.

Note: One of the most important contributions of the black legislators of the Reconstruction period was their support of public education. Due to their efforts, the 1868 Constitution called for free general public education in the State of Georgia (though it did not begin until 1872).

****SS8H6 e. Give examples of goods and services produced during the Reconstruction Era, including the use of sharecropping and tenant farming. ***Reconstruction Jeopardy link

The end of the Civil War left Georgia in dire straits. From northwest Georgia to Savannah, the state was scarred by Sherman’s devastation of the region. Warehouses, factories and railroads were burned as well as farm implements and other means with which to produce were destroyed. Burdened with a serious labor problem and a banking structure that suffered from the failure of war, Georgia’s economic outlook was dismal.

As the war ended, Georgia farmers (particularly those in Southwest Georgia) were determined to sell the cotton they had in storage. Farmers and plantation owners speculated that future cotton crops would depend on an adequate labor supply. As time progressed, large plantations were sub-divided into smaller farms but the total acreage planted dwindled. The number of coastal farms increased as rice plantation lands were subdivided and sold to new owners.

Georgia’s over-emphasis on cotton production, however, continued to leave the state in distress and to endure continued hardships. Even though it was suggested to “cultivate less land, use more fertilizer, and economize on labor” in 1867, Georgia farmers continued to plant enormous amounts of cotton as cotton prices suggested grand profits. However, the season would be a failure. Repeated crop failures left the state struggling for many years.

During 1865 – 1872, Georgia farmers did grow wheat and corn but diversification of agricultural crops was not to come until the appearance of the boll weevil in the late 1910s.

As restrictions on trade were removed, goods from Northern manufacturers filled shelves of burgeoning businesses in Georgia cities. Buying goods on credit allowed Georgians to purchase items that they did without during the war. Banks eventually opened to take care of the monetary needs of Georgia’s people. Retail stores, often operated by Jews, Northerners and sutlers (people who, during war, followed armies and sold provisions to soldiers), populated the major cities of Atlanta, Savannah, Columbus, Augusta and Macon. Atlanta, though three-quarters destroyed by Sherman’s army during the war, experienced rapid growth due to the dedication of rebuilding the railroads. With 20,000 people moving to Atlanta by 1867, the city was experiencing growth better than ever. Becoming an economic center was essential to the decision to make Atlanta Georgia’s new state capital. As the rail systems in Georgia were reestablished, Columbus revitalized its manufacturing importance in the state. In Savannah, shipping cotton resumed. Textile mills became a vital part of Georgia’s economy. While some of Georgia’s citizens were benefitting from the rebuilding explosion, many citizens struggled to make ends meet, particularly agriculturally based businesses.

After the Civil War, people in the former Confederate states suffered a serious shortage of hard currency. Due to the printing of what would become worthless Confederate money, many of the major land owners were unable to pay their labor forces, while the members of the labor force were unable to find work that paid adequate wages. In theory, the labor institutions of sharecropping and tenant farming should have been mutually beneficial to both sides where “cash poor” land owners provided land and other resources to the laborer in return for the laborers’ work on the farm. However, landowners soon found ways to keep their employees indebted to them in hopes of preventing them (both poor Blacks and Whites) from gaining the ability to purchase their own land. This also stifled their ability to take leadership roles in the cultural, economic, and political arenas of the South.

There were many similarities between a sharecropper and tenant farmer. Both usually consisted of poor and illiterate blacks and whites. Both agreed to exchange their labor and a portion of their crops to a land owner in return for land to work. Finally, both groups had to buy certain necessities from the landowner’s store which caused many to find themselves deeply indebted to the landowner and decreased their chances of getting out of the system. However, the major difference between the two groups was that tenant farmers usually owned their own tools, animals, and other equipment, while the sharecropper brought nothing but their labor into the agreement.

Sharecropping and tenant farming were entrenched in Georgia’s agricultural system until the mid-twentieth century. The system began to erode for many reasons including the Great Migration of African-Americans, along with rural whites to the North and cities in the South during and after World War I, the devastation of the boll weevil in the 1910s and 1920s, and the technological advances in farming during the time period. Though this system has almost completely vanished in the state, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, there were still 2,607 Georgians who were classified as tenant farmers in 1997. ***Reconstruction Quizlet

SS8E2 c. Evaluate the economic impact of various industries in Georgia including agricultural, entertainment, manufacturing, service, and technology.

Economic Impact of the Agriculture Industry

Blessed with a relatively mild year round climate, Georgia offers tremendous opportunities for the agriculture industry. Taking pride in their work, farmers utilize modern conservation and production practices that help protect the environment and grow healthier, safer crops. As Georgia’s leading industry, a well-established business infrastructure combined with the resources of higher education facilities enable agribusiness firms to take new products to market faster. Georgia is a leading producer of commodities like soybeans, peanuts, cotton, broilers (chickens) and blueberries and is developing new products such as wine, cheeses, ice creams, peach products among other goods. During 2012, the Census of Agriculture indicates that Georgia’s agriculture industry sold more than $9.2 billion worth of agricultural products. The census reveals that more than 42,000 farms operated with 9.6 million acres in production. More than 17,000 of the farms raised cattle, both beef and dairy cows. The state’s forestry industry contributes $17.7 billion to Georgia’s economy and supports 73,300 jobs in the state. Georgia boasts the most commercial forest land than any other state. In 2011, $72.5 billion of Georgia’s $786.5 billion economy was related to Georgia’s agriculture industry. This industry, however, is a primary source of unemployment in the state.

Economic Impact of the Entertainment Industry

A variety of enterprises comprise the entertainment industry. The arts, film/TV, music and tourism businesses impact the state each in its unique way.

The arts and arts organizations are important to tourism and local economic growth. The arts significantly offer cultural opportunities to Georgia’s citizens, creates jobs, supports arts education, and helps revitalize communities. Creative industries in Georgia represent a combined $37 billion in revenue, and includes 200,000 employed generating $12.1 billion in earnings, and $62.5 billion in total economic impact.

The film, television, and interactive entertainment industry is booming in Georgia. Since 1972, 800 film and television projects (short term and long term) have provided job opportunities to 30,000 working professionals. A growing digital media industry, university developed talent, abundant tax incentives, proximity to a well-connected transportation system, and location diversity for filming are among the reasons that Georgia has become a “camera ready” state. In 2015, Georgia feature films and television production generated an economic impact of $7 billion. Qualifying productions can earn 20% tax credits and additional credit for embedding a Georgia promotional logo in the film’s title or credits.

The music production industry in Georgia has a well-known history of producing celebrated musicians. Metro Atlanta has recently become recognized as an industry hub for music production. The industry has generated approximately 9,500 job opportunities in the state and approximately $3.5 billion in revenue per year. The music industry generates about $50 million in tax revenues for the state per year. The industry has impacts beyond the music production industry. The network of support industries that are associated with music production increases the overall impact of the industry on Georgia’s economy.

The tourism industry in Georgia provides a $59 billion impact on the state’s economy. As the fifth largest employer in the state, the industry supports 439,000 job opportunities, or 10.3% of all payroll employment in the state. Taxes of $3 billion from the tourism industry were pumped into Georgia’s economy in 2015. If Georgia’s tourism industry was absent from the economy, each Georgia household would have to be taxed an additional $843 by state and local governments each year.

Domestic travel to Georgia brought over 102 million visitors to the state in 2012, an increase of almost 4% over 2014. Leisure travel was up 3.3%, while business travel increased at 4.8%. International visitors increased by 2.4% to an estimated $3 billion in 2015. While visitor volume increased by 13.8%, visitor spending impacted the state’s economy by $767.9 million. In response to the upward projection of tourism in the state, hotel revenue is tracking in the same direction. Hotel revenue in Georgia is enjoying another consecutive year of upward trending growth, growing by 10% to $3.9 billion. Demand for hotel facilities is rising as occupancy rose to 64.4%, an increase from 2014. Clearly, the hotel industry is reacting to the positive growth in the travel and tourism industry.

Economic Impact of the Manufacturing Industry

The manufacturing industry employs 6.4 million people creating a large workforce. However, representatives from the manufacturing sector have concluded that the industry is suffering in finding employees that have the right skills and experience to fill available positions. While many people perceive jobs in the manufacturing industry to be blue-collar and “dirty”, most manufacturing jobs pay better than average salaries, offer clean work environments, and offer significant opportunities to advance within the industry. According to Hire Dynamics, the demand in Georgia’s manufacturing industry has increased 30%, but the manufacturing workforce is not keeping up with the demand for workers. It is believed that this shortage of workers will become more severe in the coming years. The industry has become more efficient due to automation, resulting in a smaller workforce that requires skilled workers who require years of training to perform the industry jobs efficiently and effectively.

Regardless of the downward trend in the number of job opportunities, manufactured goods exports are a very strong part of Georgia’s economy. Manufacturers in Georgia produced 11.50% of the total output in the state and employed 8.75% of the workforce, a significant impact on Georgia’s economy.

Economic Impact of the Service Industry

The service industry provides a type of economic activity that is intangible, does not require storage, and does not result in ownership. Services are consumed at the point of sale. As a major component of economics (the other component being goods), services are vital to the successful functioning of Georgia’s economy. The service industry is difficult to define because it encompasses a wide variety of industries and businesses. The industry, however, can be divided into two broad, general subdivisions: customer services and professional services.

Service industries are the largest sector of Georgia's economy led by wholesale (food, petroleum products, transportation equipment) and retail (automobile dealerships, discount stores, grocery stores, restaurants) trade activities.

Most professional services, which include legal, accounting, investment management, engineering and health care, have seen a steady increase in new positions in recent years. The growth in this division is linked to three broad economic developments relevant to those services: contractual arrangements, expanding construction activity, and innovations in technology. Of the professional services, health services are expected to grow the fastest, with an estimated 30% or more rise in employment. In 2015, it was predicted that the professional services industry would maintain a 1.5% - over 4% growth rate, higher than the Georgia statewide totals.

Economic Impact of Technology

Georgia’s technology industry is growing and is currently one of the nation’s top 10 U.S. technology employment markets. Compared to other states with similar industry characteristics, employment in Georgia’s technology industry grew 2.5% in 2016. Most industry leaders anticipate that this growth trend will continue. Georgia’s major strengths in the technology industry include health technology, medical devices, software development, digital entertainment and network and cyber security. While the cities of Atlanta (the technology hub), Savannah and Columbus are the leading technology locales, the technology industry is spreading throughout the state. The payroll impact of the technology industry in the state could reach $30 billion by 2020. Georgia’s technology industry wages fall below the national average; however, technology wages are growing rapidly. From 2015 to 2016, the wage increase rate was over 6.5%, significantly higher than the national average growth rate.

While the outlook for the technology industry is promising, a major concern is the ability of the industry to attract and retain key talent to the state. Finding enough employees with the right skills to fill vacancies is a very real problem for technology companies in Georgia. Many employers have had to recruit from talent pools outside of the state, resulting in relocation costs and potential satellite offices. Industry leaders believe that a focus on re-structuring technology learning opportunities in the state’s K-12 educational system will help produce a highly skilled technology workforce. A talent pool is being groomed for the workforce in the nationally ranked programs at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Georgia State University.

Random Pictures

Heading 5

bottom of page